Ragusano - part 2 of 3: The microbiology of natural cheesemaking.

And a traditional agropastoral system on Sicily.

This is the second part of an article I wrote for The Preserve Journal. You can find Part One here. A major reason I want to continue getting articles published is to share the story of the people who are dedicated to preserving old ways cheesemaking. I always want to link cheeses and other dairy ferments to the farming systems from which they stem, and Ragusano is one of the clearest examples of this that I have found.

Wheat and Carob Agropastoralism

Guido’s family have been farming at Donnafugata since after WWII, when his grandfather began leasing the extensive pasture and wheatfields surrounding the castle. He is still cultivating wheat according to a traditional rotation practice. In this system, every 2 years the wheatfields are plowed and seeded. The wheat is harvested in the late summer and the cows let in to clean up the stubble and lost grain. The harvest results in a large amount of straw that is stored and fed back to the cows during the dry late summer and fall when there is not a lot of feed in the pasture, and into the next year as a lower nutritional supplement to the high protein pasture and carob pods.

The next year the wheatfields are allowed to revert to pasture. This pasture exhibits a range of plants including sulla, wildflowers, and a diversity of grass and herbs. Sulla is a wild/planted legume that is an important high protein plant. It’s similar to alfalfa, and is cultivated in certain parts of Sicily, where it thrives with little intervention. The cows are rotated through these fields, fertilizing them with their manure and urine. Their hoof action allows rainwater to infiltrate the soil, and be held in the organic matter they deposit, incorporated with trampled plant matter. The raising of livestock is integrated with the growing of grain, which also generates feed for the livestock. Their manure and urine is not a problem or toxic waste, but a beneficial input into the system. The herd is small, its size dictated by the amount of feed grown on the farm.

Other sections are not used for wheat, but are a type of silvopasture, meaning a combination of trees and pasture. In this case it is orchards of ancient carob trees spreading gnarled branches above native pasture (never plowed and seeded). Carob is an important export crop that is used in a wide range of foods as a thickener, or as an alternative to chocolate. The cows are kept out as the carob is growing, until it is harvested in September, about a month after the wheat harvest. The cows are then moved in following their post-wheat clean up, to eat the fallen carob pods, and graze the pasture underneath. The trees also provide shade for the cows, and the pasture grows thicker and taller under the shade of the trees. The carob processing results in a large number of pods as a byproduct, and some of this is fed back to the cows at a measured pace. If they eat too much at once, they can get digestive issues from the excessive protein. Olives are also grown in this region as a minor crop.

The Microbiology of Natural Cheesemaking

Ragusano is a naturally fermented cheese. These are cheeses that are made without the addition of the commercial starter cultures that are now ubiquitous in most of the world. I learned to make cheese by working for companies large and small in the United States, and they were all using these commercial starter cultures. Even home cheesemakers are generally stuck in the paradigm of using something that comes from a laboratory on another continent to ferment their milk.

Obviously, cheese has been made for thousands of years without these commercial additives. Just like bread can be made with a sourdough starter rather than packaged yeast, milk can be fermented with the microbes that are already present in healthy, fresh, raw milk. It is mainly Lactic Acid Bacteria (LABs) that drive this fermentation, and these can be cultivated into a starter in various ways. With Ragusano this process is done by using wooden equipment to serve as a reservoir for these LABs.

Much of the microbial community inhabiting raw milk is introduced as milk comes out of the teat. A range of microbes inhabit this microbiome, with different niches on the outside, at the orifice, and inside the teat canal. This ecology is shaped and impacted by the pasture plants the animals pass through, the bedding they lay on, the influence of the suckling of their young, the practices of humans as they milk, and the milking equipment. I feel that the modern approach of using iodine on teats can have a negative impact on this ecology. The use of iodine goes hand in hand with a paradigm that attempts to limit microbial diversity throughout the process of milking and making cheese. Healthy, raw milk full of high amounts of LAB requires healthy teat ecology. The unique milking method used with the Modicana cow leads to milk with a particular ecology.

Alongside the breed and farming practices, there is also a kit of equipment designed specifically for this cheese. The Massari family caseficio (creamery) is like a museum of antique Ragusano tools, but they are still in regular use today. There is a wooden, barrel-like vat called a Tina (see lead image at top). A separate, short stretching vat is thicker and tapers towards the top. Ricotta is made in a copper pot over a fire, that also heats water for cheesemaking. A wand made from a type of palm is used to stir the whey in the ricotta vat, to prevent scalding. While most of these tools have been abandoned in the last 80 years, Guido believes in staying as true to the old ways as possible.

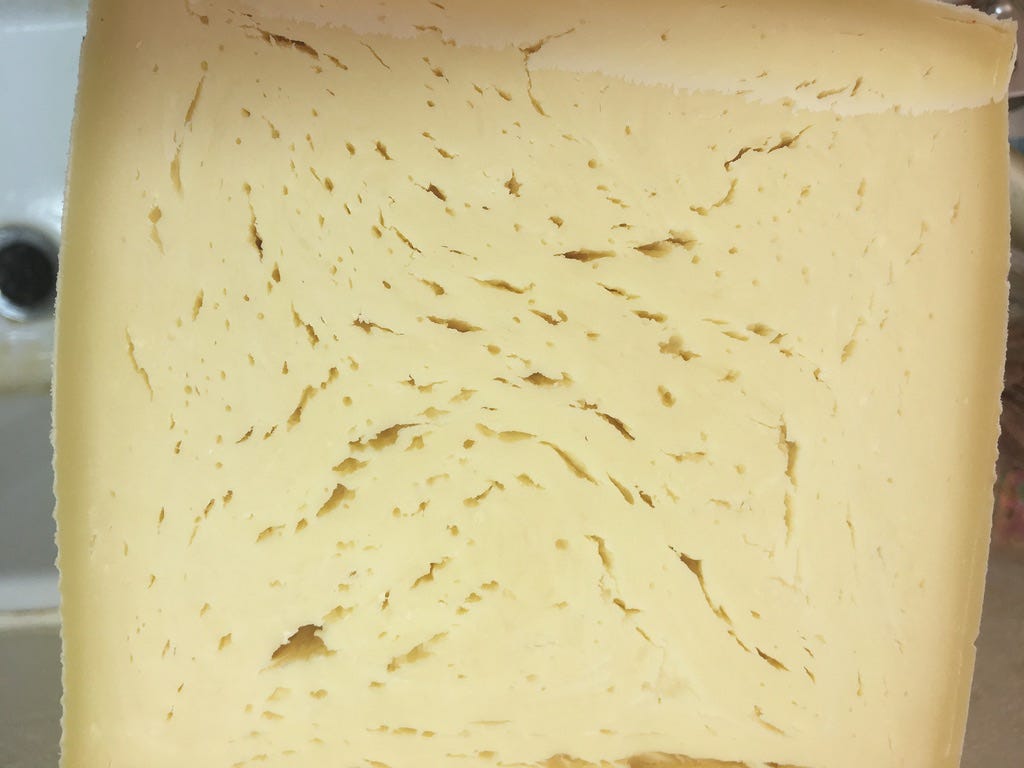

Walking into the caseficio housed in a stone building, one is immersed in a tangle of prominent aromas. Sour milk mingles with wood smoke and a yeasty aroma I associate with young cheese drying. I am in the habit of smelling not only cheeses and milk, but the tools used in these spaces. Most of these are wooden, and you can smell yeasts and sour milk on them. You can detect these aromas in the young cheeses as well, including a malty trait I identify as being a signature of naturally fermented cheeses. The finished cheese at one year old is a complex but easygoing synthesis of sweet nutty flavors, sour cream, and pleasant bitterness, along with an underlying spicy or piquant character from the lamb paste. The texture is a huge part of what makes Ragusano so enjoyable. It is like string cheese for grown ups. A vertical slice has a distinct stratigraphy of horizontal layers that can be peeled apart with the teeth one at a time. The thin layers are not smooth, but grooved, and sometimes have delectable crystal deposits that excite the mouth. It is simply enjoyable to eat, and I have a hard time putting it down.

After both morning and evening milking, milk is poured into the Tina while still warm, and curd is made. The milk is never cooled, which is crucial to its microbial balance. Storing milk at cold temperatures negatively impacts its microbial ecology from a cheesemaking perspective. The desired LABs suffer while less desirable psychrotrophic (cold loving) bacteria thrive. This is one reason why so many makers either pasteurize, or bombard raw milk with commercial starters. The cold storage of milk has created a problem that is addressed with these methods. By working with milk fresh from the udder, with an intact ecology just beginning to flourish, we can most effectively steer the fermentation towards the desired cheese.

When the milk is put into the wood vat, it immediately has populations of LABs that reside in the wood introduced to it. These LABs most likely originate from the raw milk itself, and represent a particular portion of the raw milk microbial community being encouraged by the cheesemaking process. These are acid and heat loving thermophilic bacteria that thrive in the hot temperatures of the whey that is used to wash the vat. As the fresh milk is added, these bacteria grow quickly, and are cultivated through the make process, ensuring consistent fermentation. The cheesemaking equipment is never sanitized, but cleaned with hot whey so that the desired microbes are thriving on the tools, and in the caseificio.

More than any other cheese I have looked at, Ragusano is associated with a particular breed, raised as part of a regional farming system, and milked in a way that cultivates a healthy microbial community. The method works because of the health of this raw milk, used at its optimum freshness, with equipment that cultivates this native microflora, rather than attempting to eradicate it. This cheese has a message: When one works with nature at every step of the cheesemaking process, and allows it into the spaces where cheese is made and aged, wonderful flavors and textures that are an expression of a place and people can occur.

Wonderful! I first learned of raw milk cheese and the microbiome of natural cheeses from Michael Pollan's book "Cooked". It's a fascinating subject.

Loving thinking about "cleaning" in terms of an inoculation