Butter from ricotta, stashed inside a cheese: Wild Cheese Tour part 1.

Podolica cattle, caciocavallo, and formaggi selvaggi.

I hardly knew the guy when I asked if he wanted to organize a tour with me in Southern Italy. We had met in Bra, where he throws a party on the fringe of Slow Food’s biannual Cheese festival, serving some of the wildest formaggi out there. I knew Fausto was a cheese psycho who was into the same types of cheeses and food experiences as me, and a person who is in it for the right reasons. I endorse the work of his distribution and tour company, Italian Food Hunters, which focuses on exporting Slow Food Presidium delicacies, with eye towards supporting the pastoralists and artisans through his Adopt a Shepherd program. This frenzied week would be a collaboration in which he did all the work and I documented, and we explored the possibility of putting together a guided trip in the future. He picked me up in Puglia, and we drove like over-caffeinated goats with a thirst for mountaintop water into Basilicata.

We were seeking what Fausto and a cheesemaker named Loreto (we’ll meet him in part 4) call Formaggi Selvaggi or wild cheese. In the simplest definition, Wild Cheese is what I’ve referred to as no-added-starter, a subcategory on the fringe of natural cheese. They are made through a spontaneous fermentation, in which no tangible starter is added to the milk, only rennet. The fermentation relies on indigenous raw milk microbes. Fausto and Loreto speak of wild cheese more loosely, with a list of ideals such as using farm made rennet, and aging without artificial climate controls. There is also a focus on the intention and personality of the maker, as Fausto says “I consider wild cheese a natural cheese made by wild people.” In many countries I visit, no starter culture is used, only rennet is added to milk, and salt to the finished cheese. It seems that this how rennet-based cheese has been made for the vast majority of its history. The approach is a risky one, as there is a lot of room for things to go wrong when you don’t add a starter. What I found in my travels is that there is also more room for things to go right, more chance for exceptional multidimensional flavors that express terroir.

Wild cheesemaking works best with udder warm milk (straight from milking, never cooled) that has an intact microbiota; milk that is thriving with milk souring LAB (Lactic Acid Bacteria). It often involves creameries and equipment that are home to healthy biofilms of beneficial microbes which provide primary, acid driving “starter cultures” and secondary, ripening cultures such as yeasts and molds that grow on rinds. These things (milk with bacteria in it, biofilms on equipment) have intentionally been eradicated in many countries, where we attempt to rigorously sanitize cheesemaking and aging spaces, are attempting to pasteurize the animals by using antimicrobial teat dips, and disrupting the health of herds with antibiotics and a diet that is unfit for living beings. Most raw milk in the US is essentially dead, with very low counts of bacteria, which is seen as a positive trait in the paradigm most raw milk producers subscribe to or feel forced to comply with. For this reason, I don’t recommend making wild cheese with this milk, I would use a starter, to repopulate this dead raw milk with healthy microbes.

Our first visit started where it should, by meeting the milking herd, on the ground where the milk starts. The Podolica breed is renowned for producing some of the best caciocavallo in the world. They are gorgeous light to dark grey animals with upturned white horns tipped in black. Podolica calves are blond brown, and shift color as they age. Like all regions with strong dairy cattle traditions, veal is popular here. I can’t say it enough, meat and cheese go hand in hand. We pulled off the autostrada to find the herd grazing near an overpass. It started to drizzle as we watched Italian cowboys spreading hay on the trees and brush to feed their herd. White livestock guardians dogs eyed us suspiciously, but allowed us to approach as they stayed near the calves which they protect diligently.

We drove up a maze of dirt roads and came upon the caseificio attached to a house, which manifested dream-like, suddenly appearing out of short brambly forest and pastures. The matriarch of the family waited for us with the calm demeanor of someone who knows what they are doing but doesn’t have to put on a front. Real confidence isn’t projected, it just is. Margherita Perrone wore a colorful scarf and one of the hairnet hats with a little bill that are common in Italy. She showed us the wooden vat where the cheese made that morning sat fermenting in some of its warm whey. The vat was identical to the tinas used to make Ragusano on Sicily. Here in Basilicata they are called tinos, reflecting the time when southern Italy and Sicily were one kingdom with ties to various powers from Spain. Tina means tub in Spanish. Somehow the gender got flipped, becoming tino.

This wooden tino captivated me, with stains of various molds decorating the sides. It sat next to modern stainless equipment and steam pipework in pleasant juxtapostion, covered with stains from black mold, and dried on whey splotches. It never has been, and never can be, sanitized. Wood vats are one category of naturally fermented cheese, and milk can reliably be fermented in them, if they are cared for properly by using them daily and never washing them with water. They function by soaking up whey from one batch of cheese and releasing it into the next. They are carrying a whey starter forward, but this whey is only an active for about 24 hours, after this it runs out of food and becomes inactive, enters other stages with different microbes coming to the forefront. The biofilms of microbes living in the wood are not driving the fermentation, but may impact the flavor of the cheese by growing in the milk for the short period before the curd is exposed to hot water. This will become stretched curd cheese, which requires placing the curd in very hot water, which also serves as a form of heat treatment.

Washing the vat with hot whey, and leaving some whey in the vat ensures a continuity of microbes, with thermophillic LAB bacteria likely being dominant. Washing with water would dilute the whey, and result in other, potentially problematic microbes, having room to grow. Washing only with moderately sour whey selects for desirable milk and cheese microbes, maintains them as communities in the porous wood. But it is primarily the soaking up and releasing of whey that is driving the daily fermentation, so wood vats are a modified version of using whey starters. Does that remove the cheese from the wild category I introduced at the beginning? Perhaps, but my aim is not to create and defend categorizations. My work is more to show that life will always find a way to transcend human imposed boundaries. What makes a cheese wild, and what gives it terroir, is more about microbial diversity, and certain sensory qualities that cannot be transferred into words. Certain cheese have a feral quality that I just feel when it’s in front of me. I know it when I taste it. These cheeses are best appreciated by contrast with those that have been domesticated to death, which unfortunately includes most raw milk cheeses.

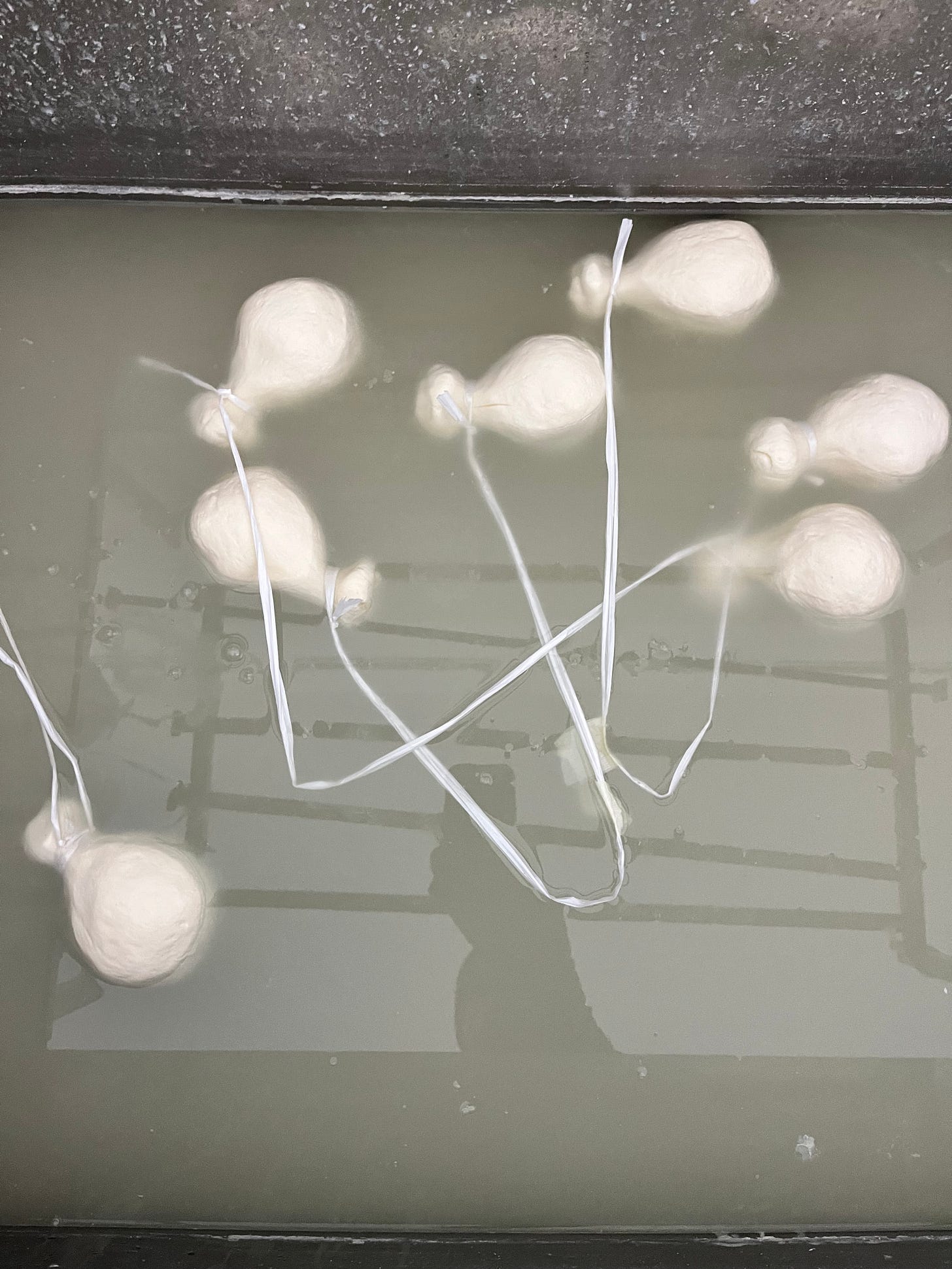

Margherita began stretching curd from the previous day into a pliable mass, a thick ribbon, by exposing it to 80C water. She formed a little pouch of mozzarella, then grabbed a ball of butter and sealed it up quickly in the pouch, before it had a chance to melt. She had just combined two of the greatest foods into one cute sculpture that could be tied to a string and hung in a kitchen, ready to be sliced and spread onto the phenomenal bread that she bakes in a wood oven just outside the creamery. The cheese is called Manteca, which is the Spanish word used for lard in some places, or butter in others. The plot thickens when we see that a Latin term, mantica, referred to a bag Arabs carried butter in? That’s highly specific. Like most food histories in Italy, there is more than two sides to this story, but I’m trying hard to stay focused on the butter cheese in front of me. It was about 9:30 am as we ate our second breakfast of bread, fresh mozzarella, aged caciocavallo, a salami with ample red chile, and little plastic cups of red wine. It seems like after my rant about how Italy has no breakfast culture, people seem driven to prove me wrong, feeding me well and getting me good and buzzed in the morning, out of a twisted combination of pride and spite. Bring it on, I say. I regret not buying one of those butter balls, just so I could slice it open and show you. But then again, now that I know it can be done, I’ll just have to do it myself.

What really perplexed me is that Margherita said she makes the butter from ricotta, by getting it cold in a fridge overnight, then washing and mashing it in cold water several times over 2 - 3 hours. It sounds like the whey proteins which make up the bulk of ricotta kind of dissolve, leaving behind the fats which are being churned out by the laborious mashing process, and coalesce as butter. I’d never heard of this. We don’t think of ricotta as having much fat, but the whey from many Italian cheeses is very milky, leading to such delicious ricotta. Whey can be ran through a seperator to obtain cream, which is used to make whey butter, in the UK for instance. There are many ways to make butter.

So it appears this cheese is an ingenious method for extracting and preserving the fat in ricotta that cannot be sold and is highly perishable. Butter has a longer shelf life, but to further preserve it, it is sealed up in an anaerobic environment, inside a cheese! It’s like the Tibetan practice of packing butter in hides, or the bog butter of the UK. There is also a cheese made in Chiapas called Bola Ocosingo in which lactic cheese is preserved inside a ball of pasta filata. I’m sure there’s a long list of preserved butters, and other cheese-in-cheese things. What can you add to the list?

This post is already too long. I keep diving off onto the side trails that make this path inexhaustibly interesting. I feel most satisfied with my writings on Substack when people comment and share, when there is engagement. So please, engage. Put butter on cheese. Tell me how glad you are that I enabled your dairy decadence.

You’re welcome.

i don't think I've piped up here before, so let me take a minute to appreciate the passion, the depth, the detail of what you're doing here. I'm not a cheesemaker (not yet, anyway) but this sure makes me want to roam, sample, experiment, and get back into fermentation in general. salute!

Amazing information and beautifully written. Thank you for keeping my feral cheese flame alive as my cows are close to freshening and I get ready for another milking and cheese making season. So much creative and lateral thinking opens up as the elemental truths of the fermentation process become part of us.