Albania: the mountain shepherds of Lepushe

The dairy culture, food sovereignty, and cheese of Kelmend

After reading a handful of articles about the isolated shepherding communities in the mountainous region of Kelmend, Northern Albania, I decided to go see it for myself. I spent a day in Tirana and met up with Bledar Kola at his restaurant Mullixhiu. He told me about the concept of gastrodiplomacy, and his work to highlight the value of Albanian foodways in a modern restaurant setting. There is a phenomenon happening in many countries that interests me, were chefs sharpen their knives in innovative European culinary scenes, then bring these skills back home to help build awareness about and support for producers of the regional foods from less appreciated places. From Tirana it is a quick trip up to Shkodra Lake where I met up with folks from an Italian organization called Vis Albania that helped me make connections and find a guide/interpreter/driver to introduce me to the families in Lepushe whose cheese and lifestyle I am interested in learning about and documenting.

I paid for a ride up the recently constructed road into the remote highlands near the Montenegro border. Passing small villages along the Cemi river, we had to slow to pass groups of sheep, goats, and cows who nap and saunter on the road. The warm summer-like Mediterranean air slowly gave way to an early spring feel as we crested a pass and looked down at Lepushe, just being revealed from the winter snow which covers the ground 6 months of the year. I met my hired guide Fran at a small cafe. He is from the next valley on this road, Vermosh, where he is a school teacher. He took me to the guesthouse where I am currently staying, and we watched Luxhja, the “mother of the house”, make cheese on her stove top. She cut the curd by first making a X in the pot, a gesture to bless the food. It is described as symbolizing the cross, as this a Catholic region in a country that is a mosaics of religions. The historical interactions of these religions is fascinating, and Albanians cannot be easily placed in religious categories as we often conceive of them. I think this X cut is functional as well, a first vertical cut to allow drainage to begin before the final cut-it takes place with a whisk a few minutes later.

Luxhja showed us the large plastic bins containing a brine aged feta-like “white cheese” that is made with boiled then skimmed cows, sheep, or goats milk. No culture is added, it’s unclear to me how this essentially pastuerized milk is fermenting in a consistent way. Individual milkings are boiled then cooled before cream is pulled, the milk is then kept cool until cheese is made every few days. I suppose the milk is being cultured from the hands of makers, storage equipment, or environment. I need to observe further. The cheeses are dry salted, the placed into brine tanks made from post ricotta whey and an unmeasured amount of salt. It’s nowhere near saturated, as the cheeses sit here for two months and only end up a bit too salty, still palatable, especially once mixed with other food. Rocks and boards keep the cheese submerged, and kahm yeast grows on the surface. Different houses have different salt levels and things growing on top, it is probably due to this that there is variation in the white cheese from one house to the next.

Until recently rennet was made here, everyone I asked about it said they still knew how but didn’t want to slaughter suckling animals when they could buy it in bottles from Montenegro. They prefer to fatten the animals for a few months until they are over 35 kilos, then sell them to local guesthouses. Looking at the bottle I recognize the words Rhizomucor Miehei: a popular source of so called “microbial rennet”, but what I would consider a rennet substitute. A few types of Mucor mold produce proteases similar to the chymosin found in the abomasums of young milk drinking ruminants. Rhizomucor Miehei based coagulants are not the same as rennet made from abomasums, and can lead to bitterness in the final cheeses. But the makers here and in so many of the places I visit see it as a step forward, and don’t understand why I am so interested in the abandoned practice of in house rennet making. I understand their position, and don’t see it as my role to tell people how they should make cheese, I am here to observe and document, and offer advice only if it is asked for. This shepherd culture is doing what it has always done, adjusting to the introduction of new technologies, making use of what is available at hand, adapting to shifting times.

That being said, I lament the loss of dairy sovereignty represented by natural starter cultures, farmer or regionally produced rennet, and wooden implements. It is in part the variety of these things, the microbial diversity they allow, that has formed the worlds library of milk fermentation traditions. Giving up these time tested methods that evolved to fit a place, lifestyle, and economy is a big step that people often don’t realize they are taking. They just see a product that makes their lives easier, or it is sold as being more reliable, necessary for modern food production, for scaling up and selling cheese on wider markets. The homogenous plastic coated fingers of the transnational chemical/biotech complex are reaching the most remote vats in the world.

I don’t think it is right to ask people to put themselves in a museum. A lot of this stuff will likely disappear, no matter what we do. My work is intended to record it before it is gone, to participate in something I find beautiful and relevant, these agropastoral pastoral ways of sustaining human communities. That and offer assistance to those who may want to promote, protect, or revitalize their dairy foodways.

There is a remarkable degree of self sufficiency up here, and this is tied to a long history of the people of Kelmend resisting being incorporated into a succession of empires by remaining in the inhospitable mountains. Vegetables and some grains are grown, but it’s really livestock and the meat and dairy products they provide that allow survival here. That, and copious moonshine made in-house from wild plums. Like most pastoral communities, they also hunt and forage, and have a wide ranging ecological awareness. The Balkans are a strong hold of “Old Ways” shepherd culture, and the people of Lepushe are my first on the ground experience of it.

Just about all of the families here have a small barn connected to or just behind their home. Hay that is cut in the early summer is storied in massive cones in the yard to replenish the hayloft which is the top story, attic like space of the barn. Below lives a small flock of sheep, a few cows and pigs, and often chickens. Lambs are born in February and March and left to drink mother’s milk until May when sheep milking begins. In the day time the ewes go out to graze while the young stay behind. The moms come back to check on the babies early in the afternoon, and at some farms the babies are let out to run with mom for a few hours. The cows are milked in the morning and then let out with the sheep. Together they are led to an area where they can graze, or just left in a large yard in front of the house, a kind of pasture lawn.

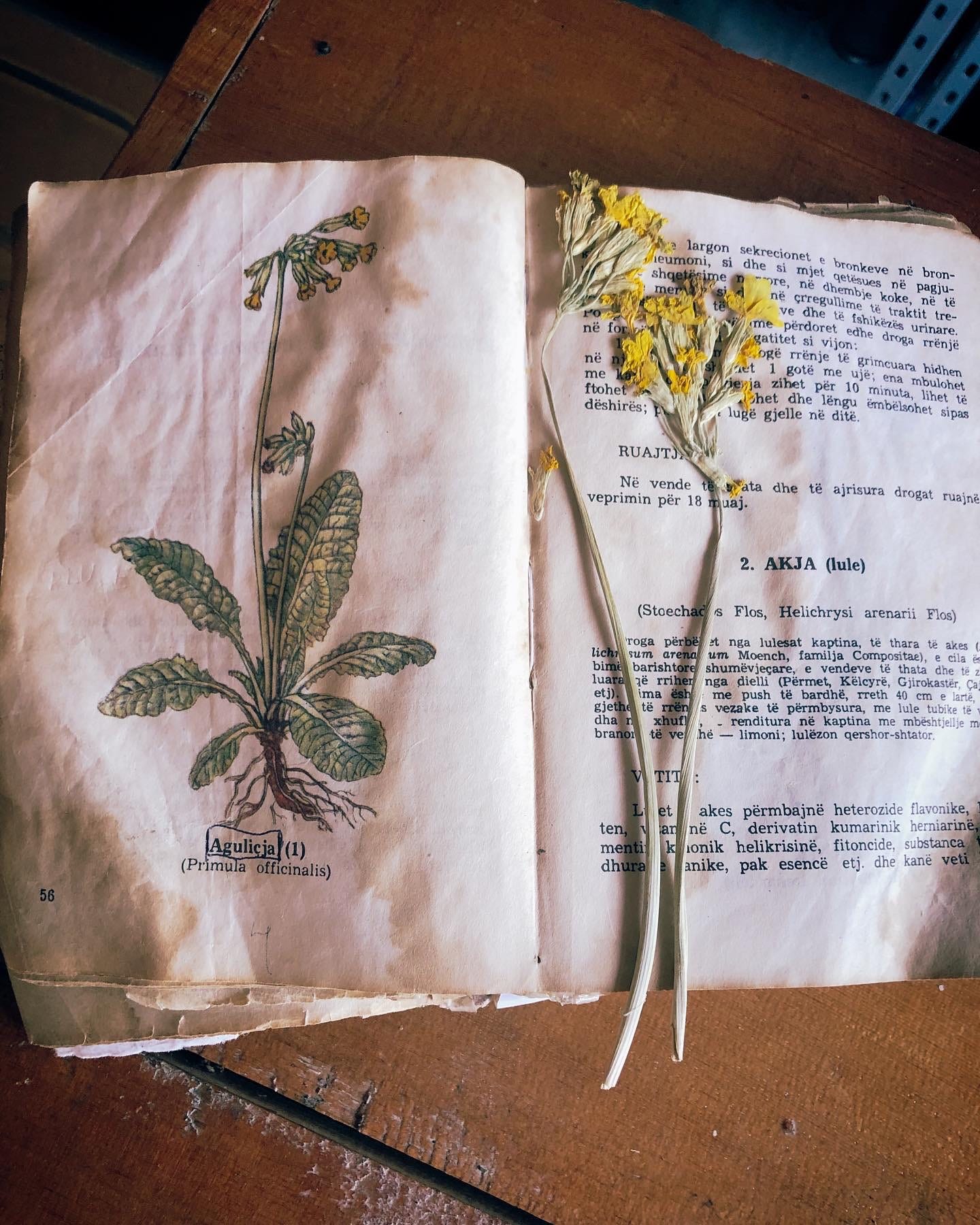

The range of medicinal plants used here is staggering, both for humans and livestock. This herbalism displays an ancient attribute where plants are assigned medicinal value based on signature, what they look like. So a certain fern with leaf parts resembling lungs is used for respiratory issues, the roots of a lily with liver colored flowers is used for liver conditions1. Many of the plants grow at high altitudes and can be picked by shepherds when they are out with their flocks, or special gathering parties go out when the plants are in their proper season.

The existence of this knowledge, although rapidly dwindling, is evidence to me of a group that has kept what I term “The Old Ways” alive. These are often proud clans or tribes who can trace their ancestry far back, who stick to their own kind, are wary of the influence of the wider world, and have fought violently to maintain their sovereignty in the face of invading armies. The question is what will become of these Old Ways as the villages are rapidly shrinking, the young leaving to seek jobs in other countries.

http://www.andreapieroni.eu/Pieroni%20et%20al.,%202005tris.pdf

This is astonishing. I think most people alive don't know these places still exist. In every country. Thanks for documenting this.

I loved your article and photos. Grateful for your documentation.