The role of dairy and preserved foods in Icelandic cuisine

And the potential for artisan cheese here

There are not a lot of dairy products or cheeses in Iceland. Skyr is the most widely known. The name is used in many countries now, but generally to refer to skim milk yogurt. Icelandic Skyr is actually a thermophillic lactic cheese that often has a bit of rennet added. (Perhaps there is no hard line between yogurt and cheese). It is drained in bags until very thick, thicker than chevre, and often watered down to get it back to a yogurt like texture, with sugar and cream added. It is a Slow Food Presidium and in the past was made with sheep milk, although now is almost always made with cows milk.

The making of Skyr reflects aspects of Icelandic culture and cuisine; nothing is wasted and high protein animal products are central. After cream was skimmed off for butter, the skim milk was used to make Skyr, which could kept be in large wooden barrels for months. A layer of whey (mysa) rises to the top, preserving the Skyr below. It became inoculated with yeast as well, likely living in the wooden vessels. Modern analysis shows a richness of thermophillic lactic acid bacteria (LABs), along with yeasts, and wider diversity in the traditional versus industrial products. People talk about leaving the milk in open pots in various locations to capture the culture, and tasting the soured milk to decide which to use as a Skyr starter. Likely it would be airborne yeasts that are landing in milk already containing LABs.

Another Skyr origin story is that milk was left near sacred rock piles, the homes of elves (huldufolk), to capture a bit of their magic! One person speculates that 11th century Skyr was made by placing sheep milk in a barrel to sour and thicken with additional milkings added until full. I imagine a delicate curd would form on bottom with whey rising to the top, perhaps what is shown in the illustration below. The sagas mention Skyr being drank, but it could have simply been watered down from a thicker state.

As in Mongolia, people relied heavily on their livestock to survive the harsh winters, and there was little farming of crops. To this day, there are few vegetable farms. Foraging and hunting supplemented the raising of animals, and these are still common. Incorporating foraged herbs like angelica, Icelandic moss, wild thyme, sea vegetables, and birch needles into cuisine was never completely lost and can be seen making a resurgence on restaurant menus. Sour whey is sold in grocery stores along with colostrum and a range of preserved meats. The idea that things like whey, organ meat, and blood are waste products is a concept of decadent civilizations. Most places I’ve visited hold these foods in high regard, or they did until the introduction of global grocery store culture, which deludes us into thinking eating flavorless Chilean grapes devoid of nutrients in winter is progress. Whey is potentially more healthy than milk, organs and blood are highly nutritious and full of minerals.

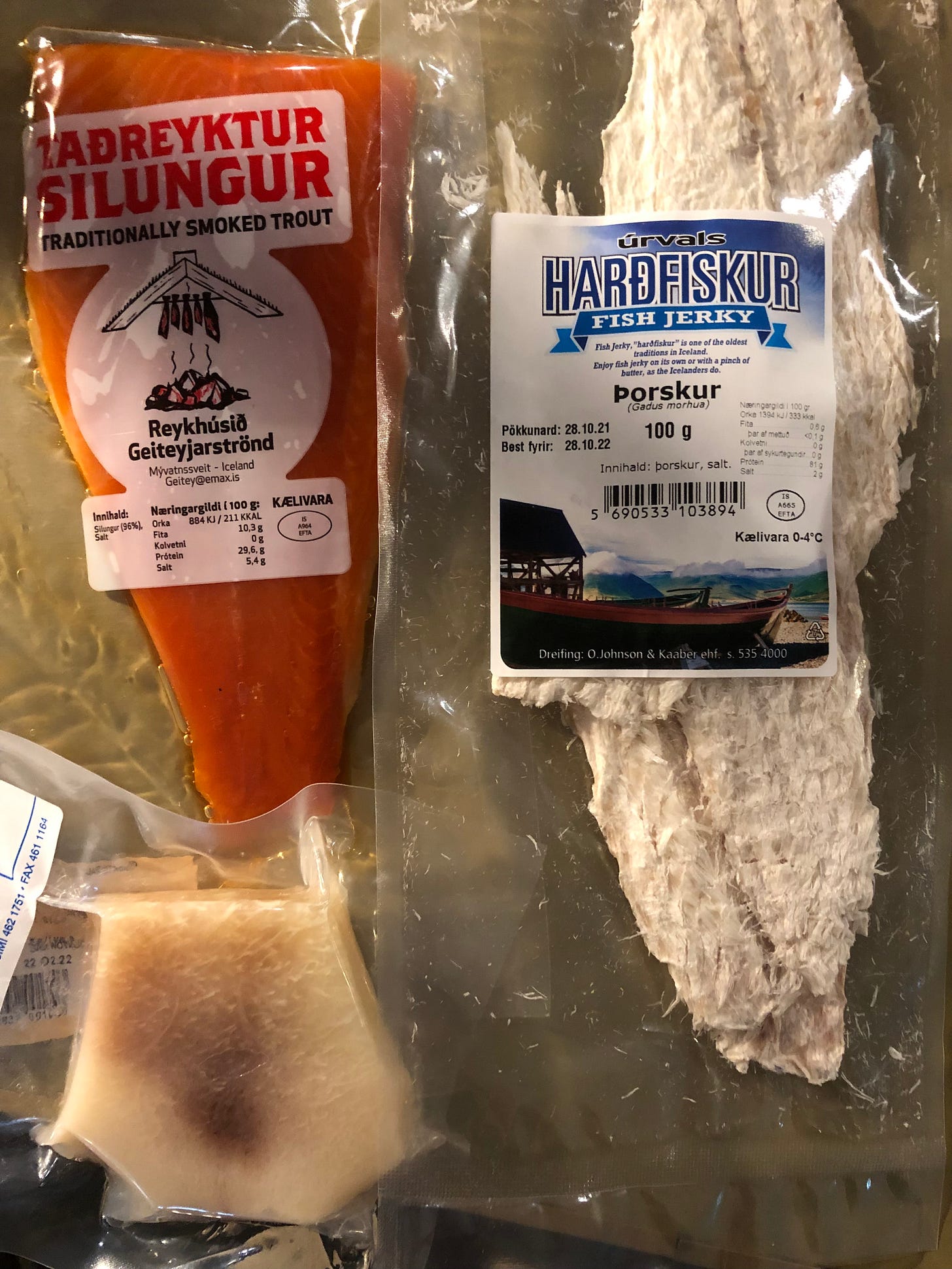

The various preserved foods here often don’t rely on salt, which was a valuable commodity in the past, when humans and livestock obtained it from eating seafood including sea vegetables. Fish such as cod are hung to dry in the cold wind. Greenland shark, which is toxic when fresh, was buried until ammoniated, then hung to dry into Hakarl. It smells horrendous: a mixture of dirty diapers, socks, and rotting animal carcass. The taste reminded me of different cheeses, a putrid washed rind at first, then piquant ammonia heat builds, like an over aged hard lactic. Trout and lamb are smoked over dung (wood is also valuable) lending an aroma and flavor that seemed like smoking gone wrong to me, black soot came to mind. This trout is eaten on an unleavened flat bread with ample butter.

A main source of preservation is the sour whey that is a byproduct of Skyr making. The ingenious dairy derived cycle that allowed people to thrive in Iceland is as follows:

Milk is allowed to sit in wide shallow wooden pans, cream is skimmed off. This was done with sheep milk as well, a thin layer of cream does form if left long enough. Cream is churned into butter.

The reduced fat milk is heated then cultured with a bit of a previous batch of Skyr. It may have rennet added to aid in the formation of a lactic curd, this may have come about to deal with a lack of temperature control needed to hold the milk in thermophillic range. The makers I met who are going for authenticity don’t use rennet. Once a solid curd forms (around ph 4.7) the curd is placed into bags and allowed to drain until more firm and acidic that chèvre typically is. I imagine the final ph to be 4.4 or lower.

The sour skim whey is placed in wood barrels and animals parts such as organs and heads are place inside to be pickled and preserved.

Another type of fermentation that is a part of this cycle is the production of silage on the farms or close by. Silage is made when hay is cut and rather than drying completely, enough moisture is left to cause fermentation, allowing winter fodder to be preserved without requiring meticulous drying and storage. Silage is considered substandard feed for cheese milk, and certain pdo cheeses, mainly alpines, forbid it’s usage. There is a potential for gas forming bacteria to cause defects in these low acid, low salt cheeses. In many northern climates silage has been a huge breakthrough, and is actually fairly modern. One farmer I talked to in Iceland spoke of spraying whey onto silage while cutting, and mixing whole beets Into the rolls of feed. It’s like sauerkraut for livestock. Not all silage is created equal, there are degrees of drying, and levels of plant diversity and fertilizer usage in the fields cut.

Iceland has the potential to make delicious artisan cheese with its heritage breeds, lack of industrial scale livestock rearing, low use of grain and antibiotics, and undeveloped native rangelands. A population of only 360,000 makes this country seem like a village, change can happen quickly. The culinary scene here is vibrant, open, and embraces as many local ingredients as possible. Any good cheese made here would be featured in restaurants and command a high price with tourists. At the moment artisan production is very limited. Raw milk is not allowed for drinking or cheese, and most dairy farmers are tied into contracts with a single cooperative.

My time is Iceland has been a next level experience for me. I feel like I have a unique perspective to share, and I can perhaps make a positive impact on the places I visit, and people I meet. I easily met most of the small scale makers here, and got to hear from chefs, brewers, educators, and farmers. I can see how hungry people here are for exciting cheeses, and the hurdles are easy to identify. My hope is that when I return here in 2023 to teach courses and advise makers things have progressed and the conversation has spread on these matters. A big thanks to Eirny @icelandcheesequeen for hosting me and organizing this leg of my journey. I owe you big time.

Do you happen to know recipes for this sort of thing? Maybe a book containing them?

Fascinating article