The Seeds Series is potentially the most important thing I have shared in written form. It didn’t come about intentionally. The words just came together, after I met The Seed Mother in India. In the Monsanto analogy I identified the big picture problem, and in Seeds of Cheese I offered some alternatives. In this fourth installment, I will address the so-called “Camembert crisis” and discuss how the loss of genetic diversity in cheese reflects an underlying sickness within western civilization.

I’m going big.

The cheese world is abuzz about the revelation that a white mold that is popular on cheeses like Brie and Camembert is becoming difficult to work with because it is losing the ability to reproduce. I again recommend this article by Josh Windsor which explains the issue eloquently. Many popular gooey cheeses with snow white rinds rely on a purchased mold called Penicillium Camemberti, abbreviated as PC. It is bought in packaged, freeze-dried form from the same companies who sell starter cultures, and added to milk to cause the white mold to grow on the rinds of small cheeses. A limited number of genetically identical clones of this mold are grown on millions of cheeses, like a pristine white lawn, where weeds are not tolerated. Immaculate, white rinds are seen as the goal, and little splotches of biodiversity (blue penicillium or grey mucor) are seen as contaminants. This obsession with purity is delusional, and reflects a wider fear, of nature, of the uncontrollable. It is the fear of life. The Camembert identity crisis is more like a psychopath being suddenly confronted with their illness. Beneath the immaculate white exterior, are some neurotic tendencies.

PC has a reputation for creating generic, uni-dimensional flavors of mushroom and hay. Many cheesemakers around the world make a PC rinded cheese, because people will buy it. These are often favored over what I consider more interesting and complex cheeses. There is a frame of reference in Brie or Camembert, and the mild mushroomy coating on a fatty puck of milk goo is very approachable. Cheese snobs talk more about geotrichum rinds, the wrinkly brainy looking things often adorning lactic goat cheeses.

In fact, most PC rinded cheeses also utilize at least one strain of geotrichum (geo), and usually a yeast as well. Makers often make blends, with the geo making up maybe 25%. Geo plays a role in the early ecology of the cheese, and gives way to the white, tall, fluffy PC. So a mixture of molds and yeast is used, but since makers use combinations of the few available strains, you end up with alot of very similar, and in my mouth boring, cheese. The point here is that I want to move from talking about rinds as being identified with one microbe, to discussing them as microbial ecosystems. A monocrop of Douglas fir planted in a clear cut with two generic understory shrubs is not a diverse ecology, and this is too often what people are making, in cheese form. There are plenty of nice cheeses that include PC, but there is usually a lot more to the rinds that just PC, it is one plant in a larger forest.

Cheesemakers often underestimate the resilience of uninvited “wild” microbes, and their ability to grow on cheese. They overestimate the ability of the packaged rind microbes to fully dominate. Some published science supports the idea that much of what ends up growing on and in cheese, even pasteurized ones, are microbes that are not introduced from packages. This paper is looking at a different style of cheese, but I believe the conclusions are applicable to this conversation. “This study confirms the importance of the adventitious, resident microflora in the ripening of smear cheeses”.

We can never fully remove cheese from the influence of unsanctioned microbes.

We can never sanitize the equipment, air, and our bodies to the point that we take these “wild” microbes out of the equation.

Why would we want to, when we see the results of that failed attempt?

What happens when we instead work towards tending diversity, respecting microbes and how they operate?

It’s easy to see the folly of a lack of genetic diversity in crops like potatoes, or bananas (I like the analogy of Cheese Sex Death here). Now we are seeing a similar pattern unfolding in cheese. The use of isolated, single strains of starter bacteria and rind microbes is quite recent, they have only been sold in freeze dried form since the 1960s. For me, the “Camembert crisis” is simply a case of the chickens coming home to roost. What did we expect would come of replicating clones of a mold, taking variation out of the equation?

This crisis is an opportunity, to reevaluate the sanity and safety of cheesemaking based on the paradigm of industrial agriculture. I hope this is a wake up call suggesting we should perhaps question the idea that purchasing microbes from biotech corporations on other continents is the best approach to fermenting milk and cultivating rinds where we live.

Between the wilderness of a cheese put into an empty cave where all sorts of things grow, and the futile attempt at sterility that is a Nano-filtered walk-in refrigerator, is a middle ground. Here, the microbes are neither random, totally wild, nor rigidly domesticated. The rind communities develop in place, and are not based on microbes grown in a laboratory. This middle ground can’t be sterilized, but can be kept tidy, allowing it to foster healthy rinds born from a symbiosis between humans, microbes, an environment, and the cheeses we craft.

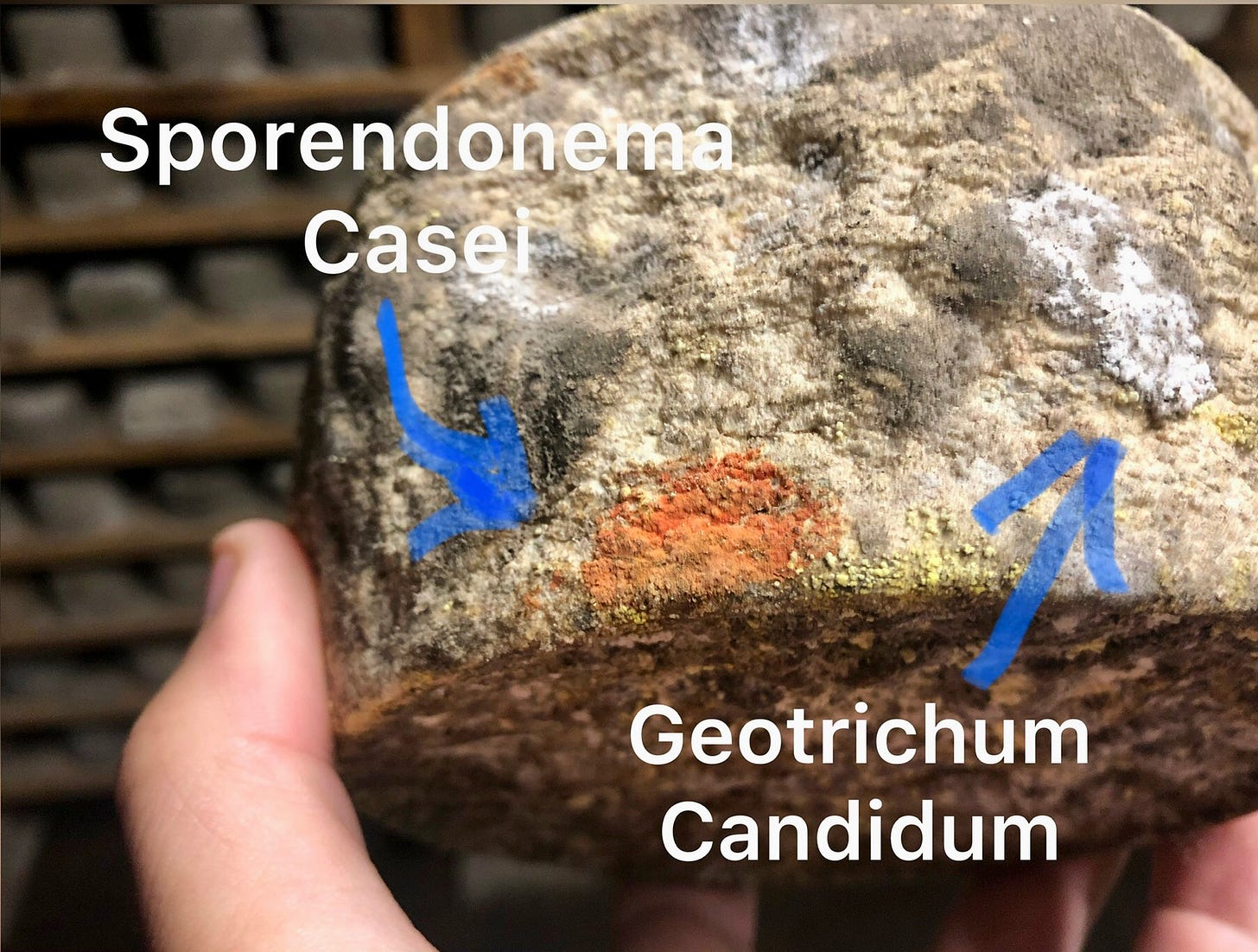

This middle ground is still thriving in cheese aging spaces around the world. I have been impressed by the global commonality of cheese rinds. In diverse places, very similar molds and bacteria grow on cheese. Similar species fill ecological niches, but with genetic variation, as shown by Sister Noella. Establishing a balance of this common cast inside an aging space takes time, and not every member of the crew will necessary show up in great numbers. Rind communities come together to fit a space, and are cultivated and selected by the temp/humidity/air circulation and human rind treatment. The types of cheese coming in play a substantial role, as they carry their microbial consortiums with them. The communities may grow on wood shelves, on the walls, and floors. Mold spores and yeasts travel around in the air, and the longer you cultivate this space and feed it cheese, the more stable the communities become.

It is my feeling that the thousands of microbial ecosystems existing in cheese aging spaces around the world can be viewed as Noah’s Arks of cheese rinds. Especially those that are not aiming at only giving space to the species bought in frozen pouches. The seed banks are there. These species are perhaps “wild”, but in places where cheese has been made for many years, there are likely distinct deviations occurring, resulting from commensal domestication that has led to the rind equivalent of heirloom starters. It may only take weeks for distinct molds to be domesticated out of wild stock, as shown in this paper that was mentioned in Josh’s article linked to above.

We need not simply look to source microbes from these external banks. We can allow the banks to flourish everywhere we make and age cheese. Many of the microbes that grow on cheese seem to come along with the milk itself, to be part of a consortium that can be cultivated and steered in different directions. The microbes have been here a lot longer than us. They surround us, inhabit us, and all life on this planet to exist. They are in the fields and barns, on the hay, thriving on the bodies of animals, ourselves included.

This is not hyperbole.

This is real talk.

The shallow “crisis” is about how we have choose to interact with a particular microbe. What it really points towards is a much wider alienation and the deeper cultural psychosis that I am pointing towards with my words, and looking beyond with my practice of natural cheesemaking.

The choice is ours. Will we continue to attempt to enslave life, letting our fermentations be guided by the folly of greed and empire? Or we will turn towards collaboration, and become conduits for expanding biodiversity, treating cheese rind microbes and in turn all life with reverence?

The tide is already turning, my friends.

These words are born from this shift.

They are coming from the sea.

From the soil.

From the milk growing mold in the darkness.

Brilliant work here! The same thing that is happening to PC is also happening to human minds right now.