Technique : North Balkan brine aged “white cheese”.

A method I observed for making a soft, feta style cheese.

Soft White Cheese Technique of the Vasov family:

See the video at the bottom of post for a demonstration.

Also, you don’t need a pH meter to have a general sense of pH. I will discuss other ways of estimating pH in a future post.

1. Milk warm from the udder, or heated to 33C (93F) is placed in the cheese vessels. If using a thick pot, pre heat it. If a thinner pot, place in a water bath of 34C water.

2. A starter culture is added, see section A below.

- Rennet is added at same time, and a timer started.

3. Flocculation is observed (point at which milk shifts from liquid to something thicker).

4. The time it took to reach Floc is multiplied by 5 or 6 to give you an estimated cut time. See section B below.

5. The firm curd is cut vertically into 2.5 - 5 centimeter squares (1-2 inch), which are then cut horizontally while ladling out with a shallow metal bowl, or wide, shallow ladle.

6. The curds are placed in draining forms, preferably and single large rectangle lined with cheese cloth.

- the cheese will not be flipped, the cloth is used to cover the whole mass, and weight applied.

7. The next day, with the pH close to 5, the mass is cut into squares and placed in a strong brine for enough time to get 50% of the final salt content in. This timing will be determined by each maker.

8. The cheese goes into its storage brine, see section C below. After being kept below the brine in a cool space for 2-3 weeks, it is ready to eat. Some reccomend waiting longer. Or aging for 2 weeks in a warmer place (the cheesemaking room) before being moved to a colder zone (cellar or refrigerator).

This is the first technical cheese piece I want to offer focused on a method I observed. I will combine this with a discussion of my take on brine preparation and maintenance. I hope it is useful for makers, interesting and informative for mongers and cheese fans, fermentistas, and culinarians in general. This is the knowledge I feel ready to drop for the paid subscribers I am affectionately labeling “Trekkies”. Thanks for joining the trek, let me know how this test run makes you feel.

Known as “white cheese” in many Balkan countries, this technique of brine aging cheese is well known in the case of Feta. But be warned, in some Balkan countries, some people take offense to their brine aged cheese being referred to as Feta. In many places, the name “cheese” or the pan-Slavic Sir (pronounced sear) means this white cheese exclusively.

The technique offers obvious advantages. Storing a cheese under salt water is an effective method of preservation in hot or dry places, or anywhere that lacks a cool, humid place to store cheese. Aging rinded cheese requires some degree of care, whereas brine aging is much less labor intensive and more forgiving. It is arguable whether this is truly an aged cheese, or more of a pickled fresh cheese. It does develop flavor over time, but not in the same way as a natural rind.

I teach this cheese at my Sour Milk School workshops as an example of an easy cheese to age at home. My approach has been to aim for a firm, crumbly, highly acidic block, with lots of mechanical openings. I feel this is a great cheese to start with when using a clabber based starter propagated from raw milk. I aim for it to get fairly acidic, the pH dropping below 5. This helps develop the shard-like, crumbly texture; and sour flavor. The tendency when beginning to work with natural starters is to overshoot, and ferment fast and far, so I allow this to happen to show that the starter is definitely active. After Feta we scale things back for a tomme or stretched curd cheese with a pH above 5. This is done by reducing the amount of starter used, and adjusting things like temperature while draining, and time before salting. The idea of slowing down fermentation and using less starter can allow the beauty of your raw milk to express more, even if using commercial starters. It also counters the logic of the industrial paradigm, which tends to advocate for a fast fermentation, directed solely by lab grown strains.

The cheeses I taste in the Balkans and other countries often tend to be a bit more wild, sometimes even pasteurized ones made with commercial starters. Pleasant mild yeast flavors, and a background richness, lead to a depth that is generally lacking in cheeses made on a large scale according to US hygiene standards. I’m finding that the raw/pasteurized, natural/commercial starter dichotomies are not absolute dividing lines of deliciousness. There are boring, naturally-fermented raw milk cheeses, and deeply rich pasteurized ones made with commercial starters. Different approaches to milk handling and udder health, the use of equipment that has not been sanitized to death, in cheesemaking spaces that are thriving with beneficial microbes, are factors in the microbial ecologies in and on these cheeses.

The point is that milk matters, the breed, feed, season, and farming practices are factors that will affect the flavor and my focus point here, texture of a cheese. This is why I resist giving a straight forward recipe. Because raw milk from a small herd is not a universal, homogenous substance. Let’s celebrate this awe-inspiring, complex nectar of motherhood, rather than trying to standardize and simplify it.

I want to explain here how I think you can go about creating a high moisture, soft feta like those I have been enjoying in Serbia. They can have a range of textures, but none of the four I have sampled has been crumbly. They have variations of pleasant and light yeastiness. I was curious how this is achieved, and was able to see it made today, on a small farm where sheep and goats are milked.

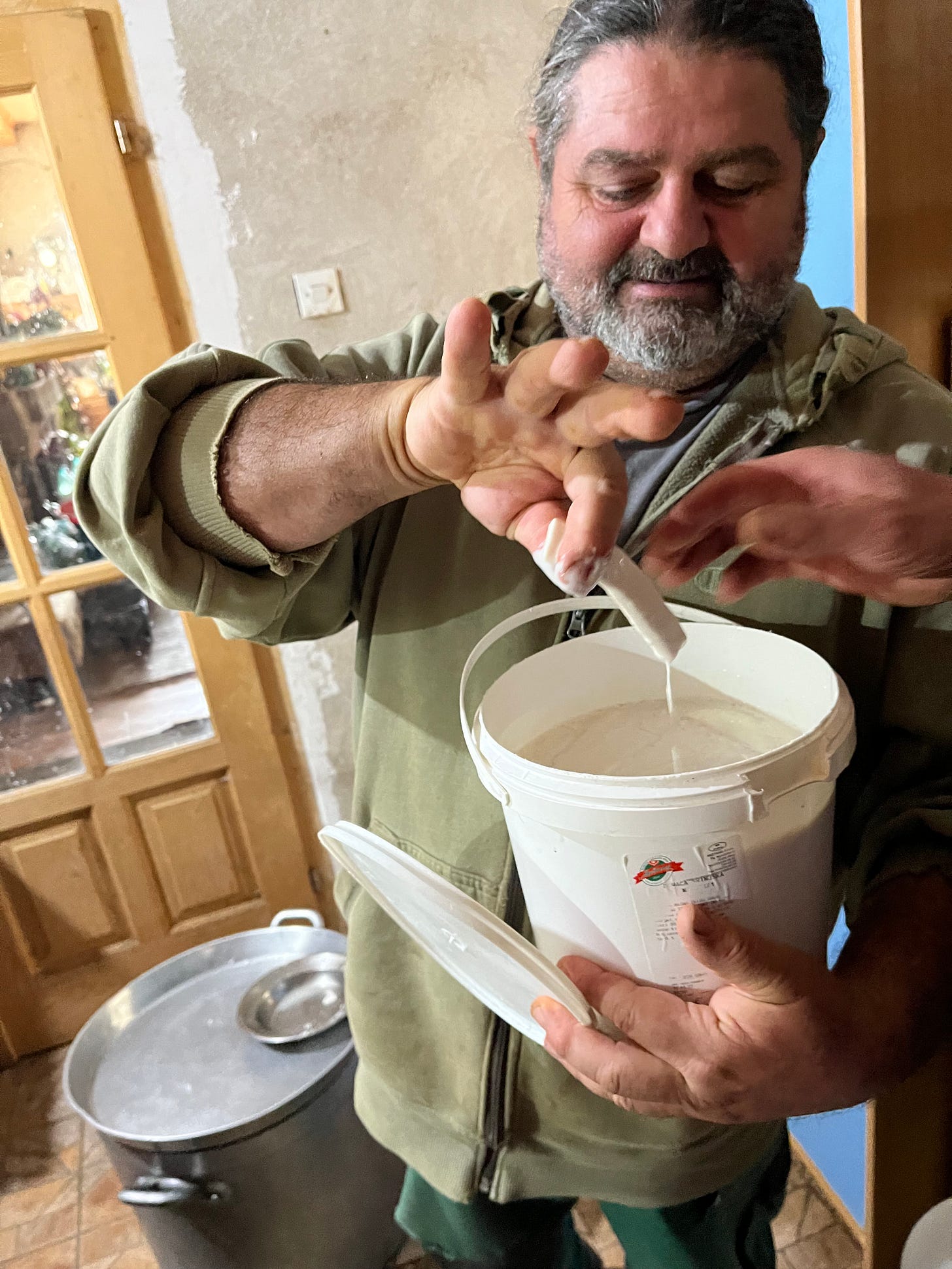

A. Milk still udder warm is never cooled or heated.

A herd of about 40 alpine goats were machine milked into large buckets for a total of 60 liters. The initial few squirts was stripped by hand and discarded. No products were used on the teats, they were not washed. The milk was carried inside immediately after finishing the last goats, and placed in a thick, pre heated stock pot. A starter culture is added called Kiselo Mleko, sour milk. It is essentially a strained, mesophillic yogurt. I am not sure how active it was, as it is not fed daily. I have doubts that it is actually doing much. The cheese could simply be fermenting from the bacteria native to the raw milk. What I recommend is using a clabber-based starter at peak activity, culturing at a rate of .5 - 1.5%. The amount used will depend on how you maintain it, what the microbial health of your milk is, and many other factors. But for this soft feta I feel we should aim for a final pH just above 5, so you should be able to use a light dose if your starter is strong. Of course a commercial starter can be used as well, but I still recommend going as light as possible, if you want the nuances of your raw milk to express.

Different styles of cheese have different levels of risk of spoilage, or being vectors for illness causing pathogens. In general, a cheese with a pH around or below 5, stored anerobically in a highly salty solution is a fairly safe cheese. Relative to a washed or bloomy rind where the pH goes up during aging. So I think this a great style to experiment with the throttling of starters to get wider expressions of indignenous raw milk microbes, or other sources of microbial terroir.

B. Longer coagulation for a softer cheese.

The starter and rennet are added at the same time. The curd is left to set for an hour, covered in thick blankets to hold the heat. I noticed they didn’t even check it until 73 minutes ( I always start a timer when rennet goes in, even if I’m just observing. Time matters). The curd was very firm. If this was a hard cheese, I would say we should have cut this coagulum (the 3D gel matrix that milk is transformed into through coagulation) at around 30-40 minutes. The longer coagulation proceeds, the firmer the curd is at cutting, the more moisture is getting locked in the coagulum. As counterintuitive as this generalization sounds:

You cut a softer curd for a harder cheese, and a harder curd for a soft cheese.

To mimic this make, I would monitor flocculation and multiply by 5 or 6 to determine my estimated cut time. Whereas for my firm feta, and most semi hard cheeses, I use a multiplier of 3.

The cut was performed by cutting vertically in both directions to get 1-2 inch square pillars of curd. (Watch the video to see the process). These were immediately ladled out with a lens shaped metal bowl, into a prepared cheesecloth on a rectangular colander setup made from a repurposed washing machine. This ladling served as the horizontal cut, and the curd was all kinds of sizes going into the cloth. So it was not stirred, or cooked in the pot. A lot of it got mooshed into tiny fragments, and the whey came out quite milky. Perhaps a large curd size left to firm up for 5-10 minutes with a few light stirs would lead to a higher yield. But the method of ladling the curd at cutting, without stirring or cooking, leads to the high moisture content of this particular make. The curd was left in this single mass. The large sheet of cheesecloth was pulled up on the edges, rolling the mass slightly, releasing more whey. The cloth was folded over the top, carefully and tightly.

For the press, a pan that fit exactly was placed on top, and containers full of water put on, after the cheese had been draining for maybe 10 minutes. It was 60 kilos of water, the same weight as the starting milk. I was shocked that it went on so soon, and didn’t crush the curd, perhaps it does to some degree. This was left on for 8 - 12 hours, and then all but 10 kilos removed as it presses overnight. The equipment used is important, such as the type of cheese cloth, and perforations of the draining form. This is one reason I can’t give a simple recipe. I share techniques that must be adjusted to fit your milk, equipment, and desired goals.

This shows that pressing doesn’t actually lead to a harder cheese. The firmness is mainly determined in the vat, by how much moisture is removed before pressing. Pressing shapes the cheese, alters it’s internal structure, and helps remove the whey that is in between the curds. The cheese is never flipped, so this heavy press is likely necessarily to obtain a closed up mass, with smooth, well defined surfaces. This aspect of the process will be customized for your equipment. But the single large squarish draining form is likely a component helping to get the highly creamy texture.

The next morning, the curd was salted by placing it in a strong brine made from whey. I am not sure about the percentage of salt they used, but I would aim for 18-20%. It was cut into blocks and brined for an amount of time neccesary to get about half the desired amount of salt in (that is my reading, and how I make this style). Again, this will be customized to your process, to how large your blocks are, and how salty you want the cheese and your storage brine to be.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Milk Trekker to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.