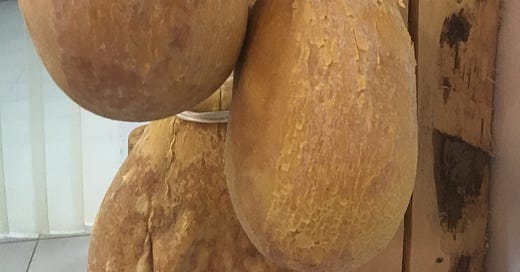

One of my favorite styles of cheese is caciocavallo, which is a type of pasta filata (stretched curd, like mozzarella) that is generally aged. Theses cheeses often have a gourd like shape with a bulging top knot where a string or rope can be tied to two cheeses, which are hung over a rod to age. This is reminiscent of the saddle bags on a horse, hence the name cacio (cheese) cavallo (horse). I’m doubtful of this name origin, as similar cheeses are made in the Balkans called Kashkaval, and the name was likely altered in Italy to something that made linguistic sense here. Or it could be based on a Arabic word for cheese molds. There is a fascinating 3 part series of articles on the possible origins of these names here : Kashkaval part 1 , Part 2 , Part 3

Whatever the origins, the aging of stretched curd cheeses offers advantages in dry Mediterranean climates. The application of hot water while stretching creates a smooth, dehydrated layer on the outside, essentially kick starting a rind to hold in the more moist interior, free from intruding molds. The aging of these cheeses is more forgiving with this rind, some are rubbed with olive oil periodically to prevent cracking. They don’t require the same high humidity as other styles, and are more forgiving of temperature fluctuations so can be aged in a simple cellar or cool room. In the past very few makers had access to high moisture caves with shelves, so cheeses that can be simply hung in a cool food storage area were favored. The hot water stretching is also a form of heat treatment to eliminate potential defect causing microbes, which can easily proliferate in milk stored without refrigeration in hot climates.

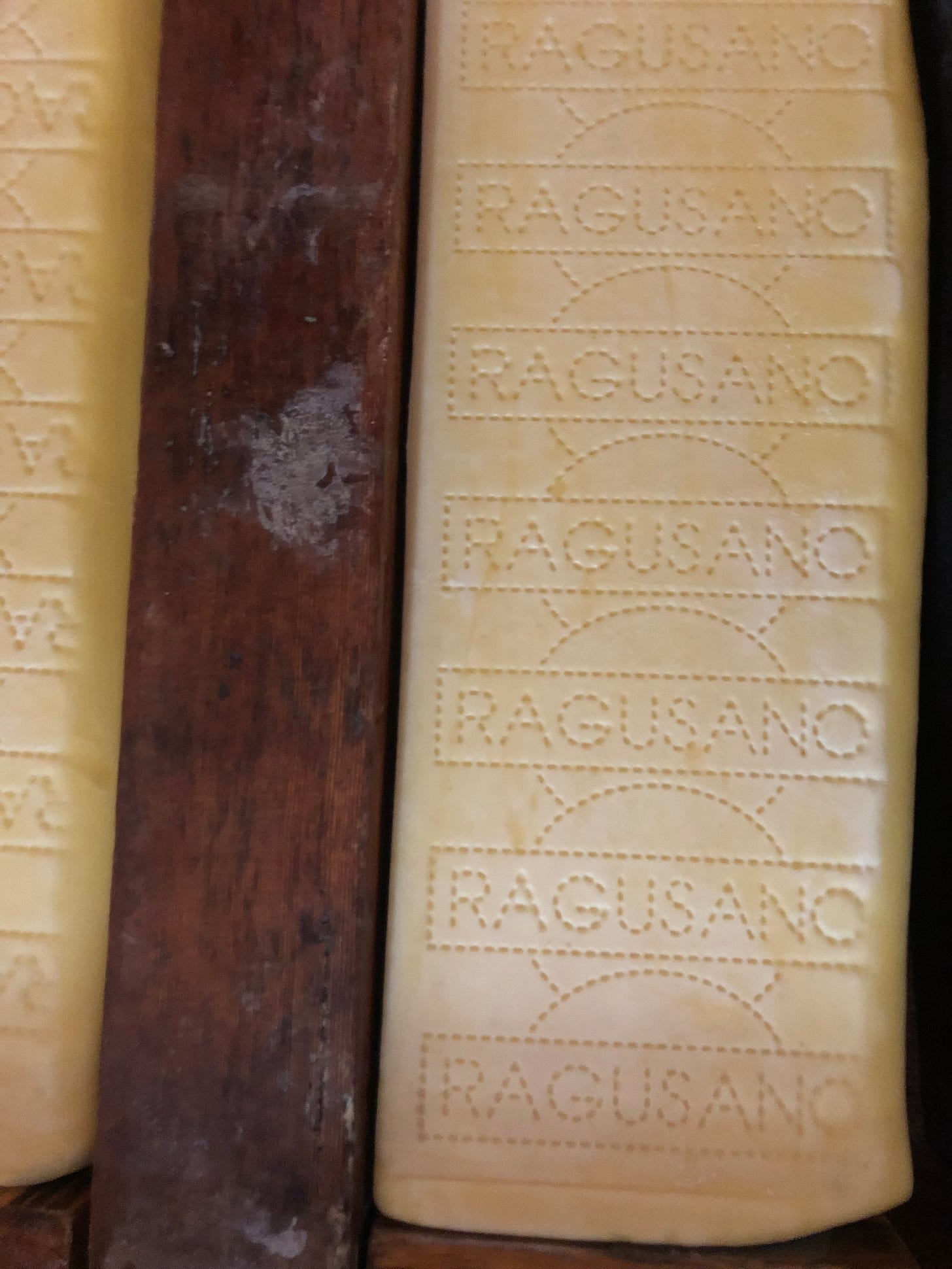

For me, the king of caciocavallo is Ragusano DOP, made in the southern Sicilian province of Ragusa and parts of Siracusa. It is only made during the rainy season, and the start and end dates for DOP production vary from year to year. Among the DOP requirements is the use of a wooden vat called a Tina to make the initial curd in. No starter culture is added, but the Tina serves as a reservoir for beneficial lactic acid bacteria, and is only washed with hot whey. The species in these bio films have been documented: Link. This curd is held for 24-48 hours while it slowly ferments until it can be stretched. A single giant (15+ kilo) curd mass is carefully shaped to minimize interior air bubbles and form a smooth surface. This is placed in a large wooden box called a mastredda where wood blocks are arranged to give it its square loaf shape after multiple turnings.

All the wooden tools used have names and some are designed specifically for this cheese. The use of wood in creameries has been banned in many countries, food safety regulators rightly say that wood cannot be sanitized and can harbor colonies of microbes. This is true, but what they leave out is that the wood can serve as a reservoir of beneficial, milk fermenting microbes that can outcompete pathogens. Plenty of papers have been published showing that not only can wood be safe, it can be safer than the approach of stainless steel and sanitizer. I’m not saying we should abandon food safety laws, or attempts to prevent the occurrence of pathogenic disease. I’m saying these laws should be based on science, rather than being influenced by industrial paradigms and the sway of entrenched corporate power. The threat to our safety isn’t from people fermenting food in their homes and on small farms. It’s from large scale agribusiness, industrial food production. I’m shocked when people question drinking verifiably safe raw milk, but don’t bat a lash when buying conventional strawberries or spinach. There should be different requirements for different scales of production and styles of cheese. If you can verify the safety of your products, you should be able to sell them.

The uniqueness of Ragusano extends into the aging spaces, where thousands of cheese loaves hang from pillars. As they age, the rope bites into the loaf and creates wonderful angles and divots, giving each Ragusano a glorious imperfection. These aging spaces are milk sculpture art museums, where the functionality of the approach is revealed. You can fit loads of cheese into a space this way, with no shelves or need flip or turn wheels. Ragusano is generally aged by a dedicated affinuer who ages the cheeses from multiple farms for a fee. This division of labor allows the maker to concentrate on daily production, and works well in areas where many farms make the same cheese, a regional specialty that can be marketed collectively.

The flavor of Ragusano is sharp, with a lipase punch that increases with age. This distinct piquant spiciness comes from the lamb or kid rennet paste used to coagulate the milk. One whiff of this rugged raw coagulant will tell you exactly where the more subtle flavor in the cheese comes from. A big part of this cheese, and other that I adore, is its addictive texture. It’s enjoyable to eat, the mouth wants more of it, it’s fun to chew on. It’s like string cheese for grown ups, distinct layers peel apart and have a pleasant chewiness that is firm but juicy. Words can’t do justice, just try to get your hands on some of this masterpiece. 80% of it never leaves Sicily, so good luck.

The Ragusano made by Guido Masseri at Donnafugata Castle is the opposite of industrial food production. It’s the end product of a labor intensive craft, a well established agropastoral farming system combining pasture with carob and olive trees, as well as wheat fields. When I first saw this make in 2019, I was shocked. It takes so much effort, time, and specialized tools to make this, why not just make a simple Tomme? To get the specific flavor and texture of this cheese requires these steps and tools, and Sicilians have a deep cultural connection to this cheese. There are no shortcuts. I admire makers who specialize in making one cheese well, following an old method that hasn’t been sacrificed to the compromises of modernity. This cheese is a statue of defiance, a statement of pride, a result of generations working out the details and designing the tools to achieve a beautiful expression of milk preservation, suited to the climate and economy of the region.

I will elaborate further on this agropastoral system in a future post, as well as discuss the importance of the Modicana cow to this cheese. I hope you enjoy the photos here from my visit to Azienda Massari Donnafugata where Guido Masseri is one of the last making Ragusano solely from the milk of Modicana cows, using the old implements, heating water and whey with fire.

Really enjoyed that!