While volunteering with the Cangemi family in Valle Del Belice, Sicily, I have observed an ingenious way to divide one days milk into 3 or more cheeses. The same curd that makes hard, large wheel Pecorino Siciliano can be held to slowly ferment for 24-48 hours to make Vastedda, a rare sheep’s milk pasta filata (stretched curd, think mozzarella). In the summer when it is warmer the fermentation takes only 24, in the colder winter months 48. This allows the cheesemakers to make enough of the fresh Vastedda to fill demand, with the rest of the milk going into the aged Pecorino. To top it off divine fresh ricotta is made and sold daily (besides Sunday) with religious devotion. Being able to divide your milk like this and get multiple products to be sold at different ages is a smart approach, one that the family has developed over generations.

The rainy winter months are when the best native pasture exists for the sheep to graze on; it is lush, green, and diverse forage. These are perfect conditions for cheese milk, fermented here into long aged Pecorino Siciliano. The cheeses destined to be PDO must have no visual defects at one month and can then be sold on to an affinuer who finishes them. Those not up to par can still be sold at the caseficio as Pecorino stagionato, or semi stagionato. Unlike many Sardinian and Sicilian hard sheep cheeses, the one made here has little of the piquant lipase bite found in low levels in Parmigiano, for example. It is clean, fruity, nutty, sheepy.

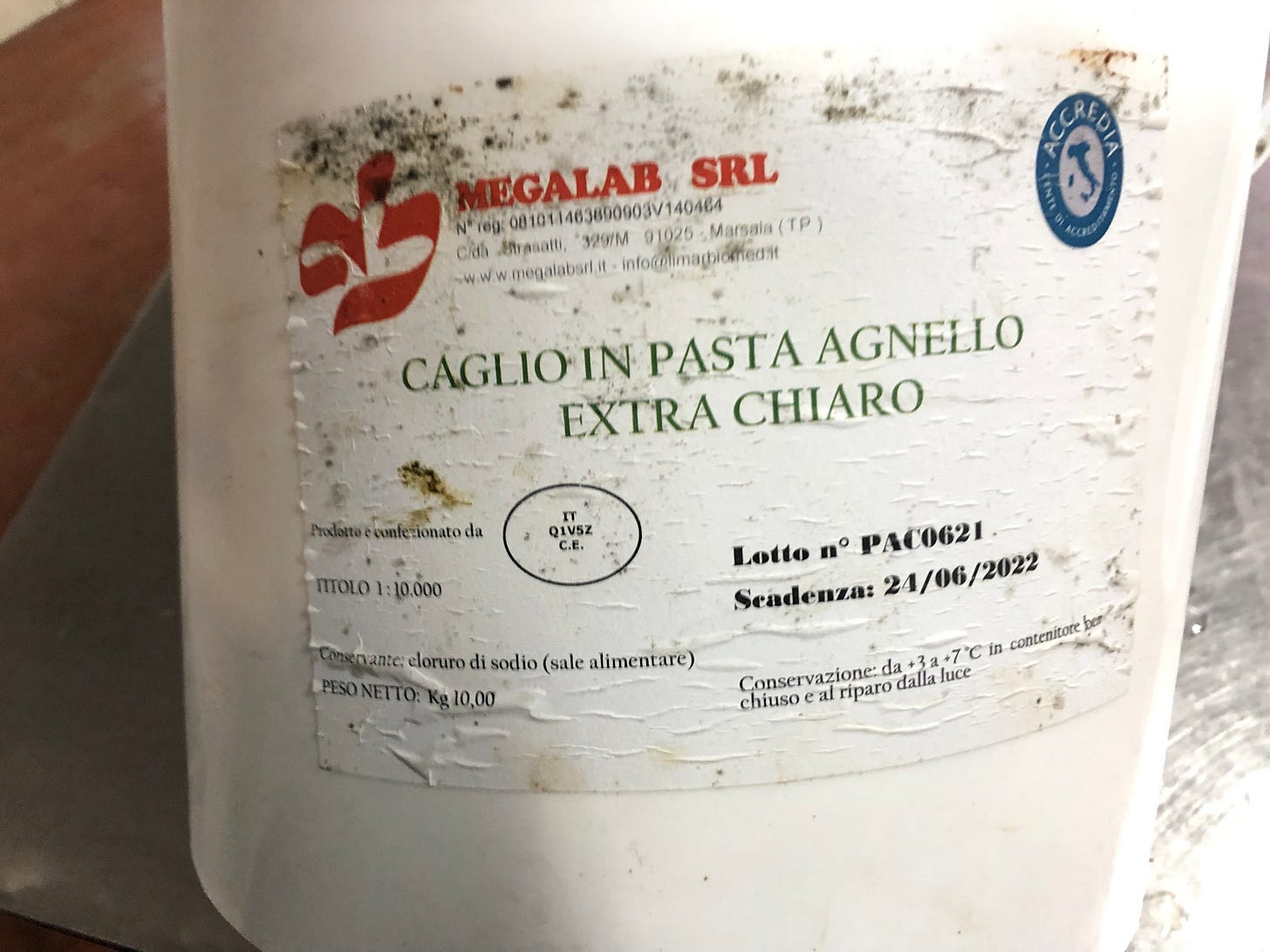

The choice of rennet has a lot to do with the strength of this bite. The PDO regulations for this cheese stipulate that it be made with lamb rennet from the island. The Cangemi’s use a lamb paste that is labeled “extra chiaro” meaning extra clear or clean. I’m assuming this means the producers wash out the abomasums (the portion of a ruminant digestive system home to coagulating enzymes) of their “cheese”, creating a rennet with less lipolytic action. The rennet paste smells lovely, gamey, with a not overpowering lipase aroma. A main component in this aroma is butyric acid, which frankly evokes memories of vomit. In large doses it is disgusting, in small many find it mouthwatering. This is one of the more challenging tastes I have acquired, and it took me time and effort to do the neural rewiring needed to enjoy cheeses that remind me of being sick. Lots of caciocavallo and other southern Italian aged cheeses have shades or punches of these flavors, and they derive from the coagulants chosen and sometimes blended (its common to use mainly calf liquid with a bit of kid or lamb paste). Choice of coagulant is a huge factor in the flavor of aged cheeses, and having a range of options is a benefit to making in places like Italy and Spain.

The portion of the days make that will become Pecorino is hooped in plastic moulds and the curd manipulated in a method called intumarre where ones fingers are used to break the curd up and release more whey. I’ve seen similar methods in Mexican cheeses such as queso fresco, where whey is removed and a texture generated through mashing breaking curd that has little acidity. After ricotta has been made, the Pecorinos are placed in the 70c hot whey for 1.5 to 2 hours as it slowly cools. This is the cook or scald step, creating conditions for a thermophillic fermentation. They then are placed into woven reed baskets to take on their rustic Homeric look. While this is considered a raw milk cheese, how raw is it? All the cheeses made here undergo exposure to high temperatures, and these temperatures alter the raw milk ecology. This is probably necessary to prevent coliform bacteria from causing defects in these slowly fermented, “no added starter culture” cheeses.

There is an absence of what many consider standard hygienic milking procedures. Teats are not cleaned, the first initial blasts of milk are not discarded, hands are not washed, poop and hair falls in. The milk is filtered multiple times to remove the debris, but in honesty it is likely the microbial richness enabled by these practices that allows the milk to ferment spontaneously, in a somewhat predictable way. The milk sits in plastic milk containers for an hour or longer before going into a bulk tank overnight. The protocol in the creamery ignores many of the modern standards I was taught are necessary. Less than pristine boots and clothes are worn while making cheese. The make room contains a cold case and customers walk right in to purchase cheese. Much of the equipment is washed only with hot water, there are wooden vats, stirring implements, and hoops. Not only is the cheese safe to eat, it’s delicious in a way I don’t feel could be recreated in the futile attempt at sterility that defines so much “modern cheesemaking”.

Vastedda is an expression of the rich creamy goodness of the milk, and the portion to be stretched is set aside in trays. After 2 days, this curd is taken from a cool space and stretched in a wooden vat. No ph meter is used, they are some how generating a fermentation that is predictable enough, with I assume a large window where the curd is in the stretch range (ph 5.4 to 5). It stretches beautifully in the hot whey left from ricotta, and is shaped by hand into balls that are plopped into soup bowls, giving smooth sides and a distinctive shape. I am used to stretching cows milk, which seems to require a higher temperature to be workable, the sheep milk curd was stretched out of not ridiculously hot whey, it appears to remain malleable at lower temperatures.

It has been amazing to spend two weeks with these sheep and cheeses, this family and landscape. I worked hard, fell in the poop, became skilled at rolling hash cigarettes while bouncing down dirt roads in a pick up. I learned much about a disappearing agropastoral system, and the cheeses embedded in and extending out of it, representations of a place, a family, a way of life.

As always, questions and comments are encouraged. What experiences have you had with the spicy lipase flavors of cheeses? How do you feel about the importance of coagulants in cheese flavor, and the lack of them in so many places? If you’re not a cheesemaker, do you find writings lien this to be relevant and informative?

I’m no cheese maker and in fact am slap dash in any of my culinary creations, often with bare feet having collected eggs from the chicken coop, unwashed hands and all the rest.

I lived in rural Sicily 20 years ago and my neighbour was a goat herd.

It took me a year before I could speak the village dialetto and when I finally could, I was able to go buy my fresh ricotta, as he did not speak Italian, having never been to school.

The goats and sheep would roam through my land, I visited other families who made their weekly breads in a tiny garage with a wood fired oven, I helped at the olive harvest, learned to salt my own olives, got very drunk too frequently at lunchtimes on everyone's home brewed wine, and so much more.

These traditional skills are precious and not practiced enough.

I really enjoyed reading what you shared, and it took me back to my friendships with these wonderful, funny and real people in Sicily where life evolves around food (and gossip).

It is no wonder that the richness of life makes its way into these cheeses that are created as part of life rather than a separate, sterile environment. The microbial reflections of our environments are the magic elements that created these wonderful and traditional foods, dirty hands and all! Let's keep it that way for the good of our palates, our gut health and our artisanal traditions!

I'm curious, with the hotter climate in Sicily, do they age in cool caves underground? I always seem to see caciocavallo hanging in normal rooms with either windows though subterranean or above ground. Do they just age cheese at a higher temperature and add more salt and allow higher acidity to over compensate? Or are there less molds in the more hot seaside climate there?