Origins, part 3: Fruition Farms, the San Juans, and road trips around the west.

Dabbling in a life of Itinerant cheesemaking.

Back in September, I posted Part One and Part Two of what I am calling “the origins series”, which tells the backstory of how I ended up doing the cheese travel trips of the last 5 years. The series will have many more episodes In the coming months.

The summer of 2013 was like a lucid dream that I’m just now waking from. It gave me a taste of the mobile life that I now live in a slightly more grown up fashion. It tasted incredible, and like someone who had gone weeks without eating, I gorged. For eleven years. Now I’m pretty full, and could use a fast.

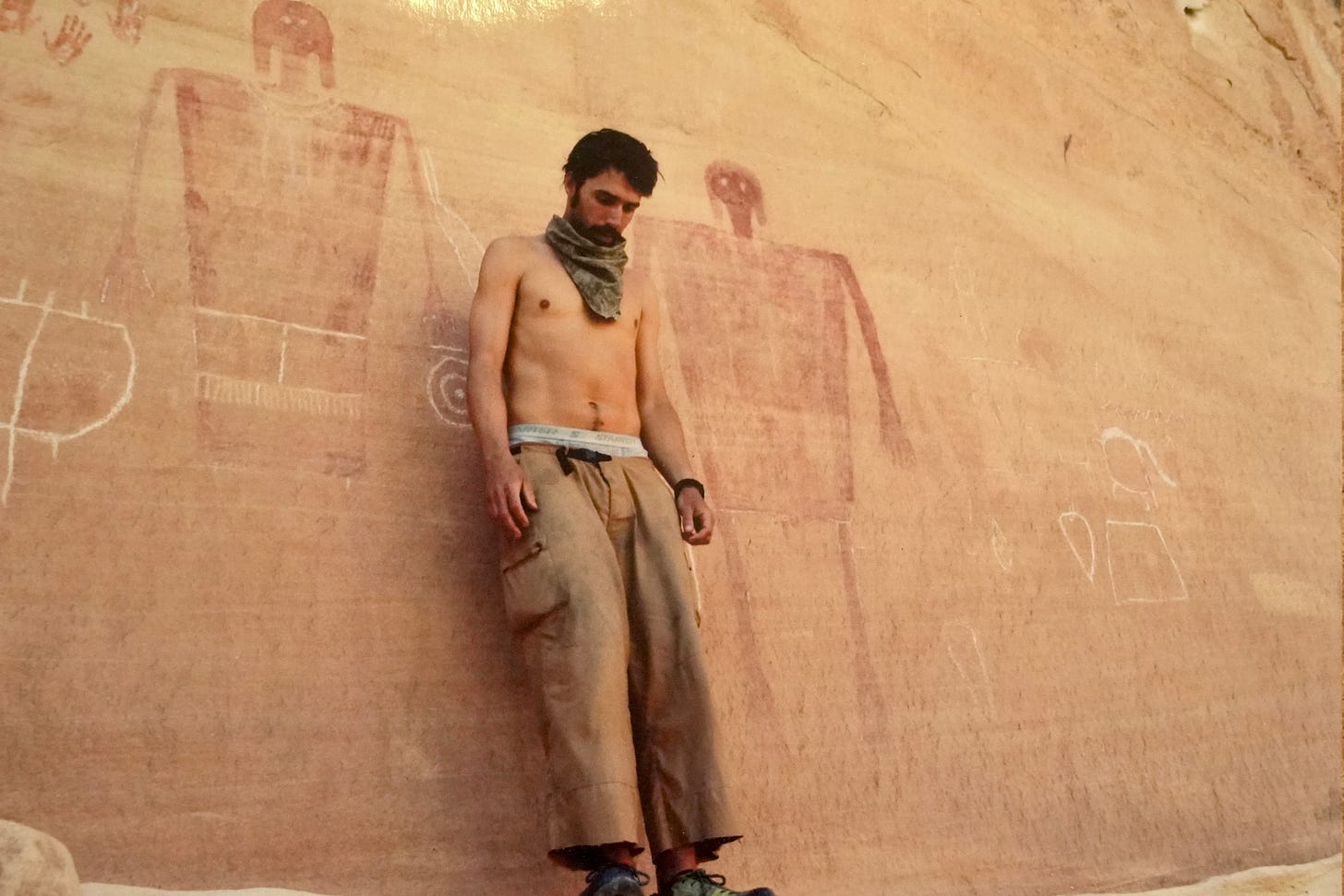

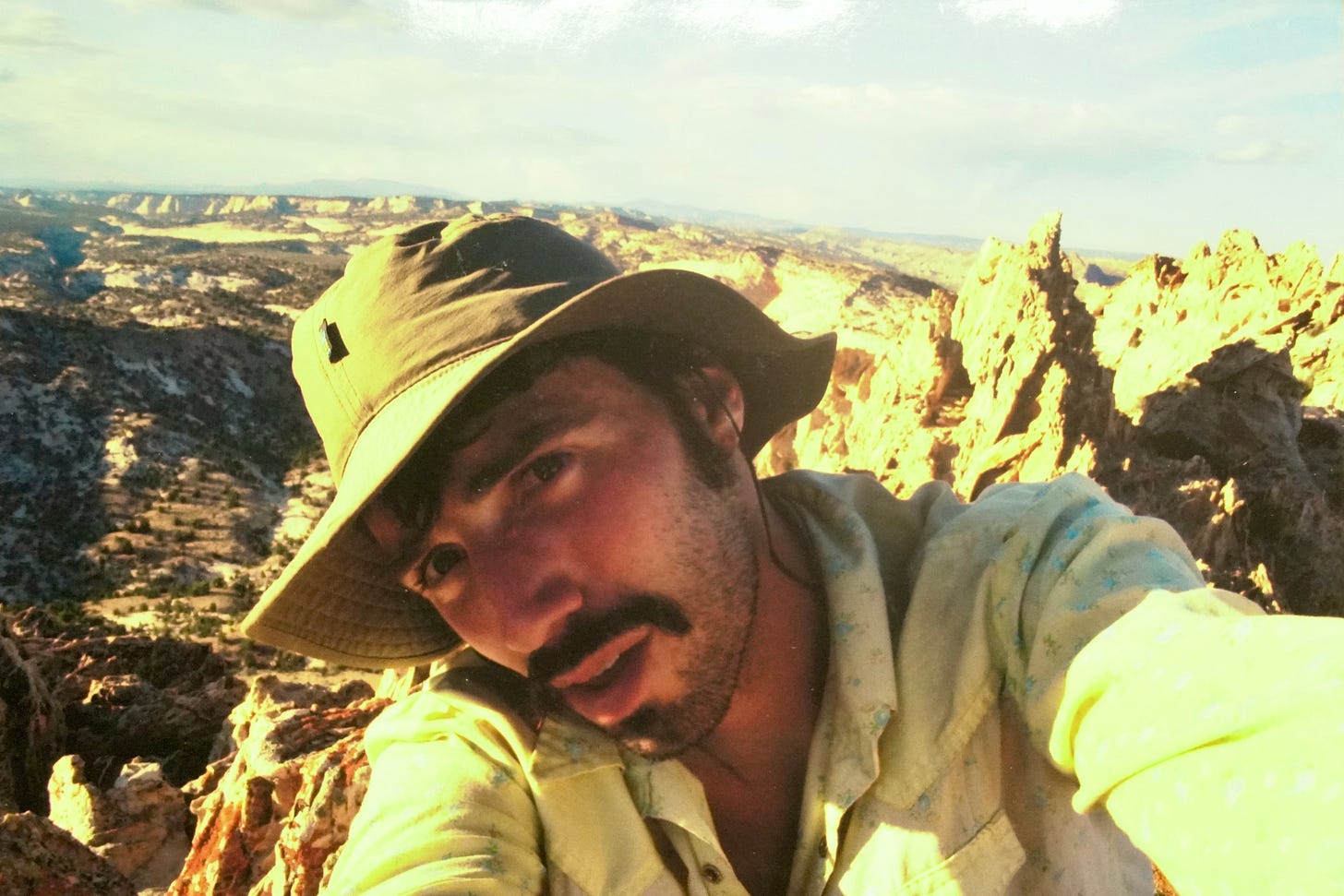

I had never spent so much time alone, sleeping outside and cooking over fires, backpacking for days on end. Scrambling down cliffs to sacred pools where I washed the sins of modernity from my skin, and lay naked on the breast of Mother Earth. Going feral. Getting back to source.

Coming home.

After this summer, my life took on a pattern of: work a job, save up as much money as possible, then quit and travel until it ran out. It was spring, and I drove through the Mojave in my shabby excuse for a custom camper minivan. I stopped in Slab City to drink with forlorn, crusty souls, then crossed into Arizona, where I ran into people going for casual nature walks with automatic weapons on more than one occasion. I saw the fortified southern border snaking through the sand, a brazen symbol of cruel futility, imperial fantasy. Many empires have attempted to fortify their borders in this way. Where did that get them? Buried in the sand. The United States of Ozymandias.

I hiked in canyons and drank cold beer next to solo campfires, sleeping as sound as a dusty dog every night on public land. Smoked two pounds of Cali herb and tried to stand on my head. Into Utah, where I was humbled and tumbled by the slot canyons of the Escalante river. Up into Colorado, where I stayed at Fruition Farms south of Denver. I was impressed with the sheep cheese operation, and told Alex and Jimmy - the two chefs who ran the show - that I wanted to work for them. I then drove back to the Northwest, to spend the rest of summer in my hometown of Port Orchard, Washington.

From the Southern border with Mexico to the Northern with Canada, without crossing either one. What is a border? An imaginary line drawn on a rock spinning through space that people die trying to cross, fight wars over. It is a symptom of the dangerous sociopath whose house we live in, whose hubris and abusive nature we try to avoid talking about. Nation-states and their fortified borders are inherently unethical. The concept of rigid, fixed boundaries is a deeply rooted aspect of western materialism, that fools itself into thinking the categories it creates, the boxes it divides creation into, are actually real. We even fight and kill over these intellectual borders that we construct, passionately defending our side against the other. Luckily, many of us realize the futility and brutality of drawing lines in the sand, then shooting anyone who crosses them. Many are beginning to realize that the truth is, all sand is sacred earth and belongs to no one. This is what I thought then, as I drove from the bottom of the US to the top. This is how I feel now, sitting not so far from the Southern border. My heart knows, and I let it guide my mouth to speak these words, that maybe your heart will hear. All sand, water, dirt, blood, air, rock, plant. Alive and Holy.

I arrived to start my third cheesemaking job just as the winter snows began at 6000 feet. Working at Fruition Farms appealed to me because I was involved with caring for and milking sheep, as well as making and aging cheese. To expand my knowledge out of the creamery and learn to work and live with livestock was a goal of mine. Living in a little apartment that was connected to the barn where the sheep stayed, I could hear the lambs at night, bumping into the wall we shared as they stampeded in a circle. Lambpedes. I loved the process of moving the sheep, filling feeders, then enjoying the ambiance as the flock settled in to munching down their hay and alfalfa. That feed came from many places, and the flock did not have pasture to go out on. I began to notice that the cheese would shift when we switched to a new feed. It would act and feel different, as the milk changed and the animals adjusted to the dietary shift. The importance of feed and animal health for milk and cheese quality was dawning on me. I began to see that when the feed was all imported, this placed an important variable out of the hands of the cheesemaker. How could a cheese possess terroir, a taste of place, if the feed is coming from hundreds of miles away, grown in unknown conditions?

One aspect of sheep dairying that I found highly enriching was lambing season, when we had to be present to assist with births, keeping lambs and moms in pens, giving shots and putting ear tags on the babies. Some of the lambs required special care, such as bottle feeding or being brought inside to stay warm. Not all the lambs make it through the cold, and some seem to be born without much will to live. Even those who become strong and fat will be killed and eaten by humans. Milk comes from this cycle of birth and death, and by participating in this process I realized the full responsibility that comes with drinking milk and making cheese. The intimacy with motherhood and the nurturing of new life was new to me. It was also an intimacy with death……with killing and eating members of the flock. This intimacy is often missing when milk is simply delivered to a creamery, divorced from the wider reality of its source. Rather than being ethically conflicting, it was enriching to face up to and participate in this reality.

To live, is to kill.

Even if you stopped eating, you can’t take a step or a breath without killing fungal spores, bacterial colonies or insects. Vegetarians kill living, sentient beings, such as plants and mushrooms. They are just killing things that can’t run away, which doesn’t imply any sort of moral high ground in my book. That high ground seems like a dangerous place to stand anyways, based on a denial of basic truths.

Waking up, putting on many layers of cloths, walking the sheep down to the milking parlor. The air is crisp and saturated with smells of delayed, overwintering compost, wet sheep, and dry hay. After milking, I would feed the sheep and get the cheese started. I usually had help, but if need be I could finish up the cheese in time to also do evening milking and feeding. We made an aged raw cheese, a pasteurized bloomy, and whole milk ricotta, which some would argue is not ricotta at all. I learned so much about cooking and food preservation, working with the chefs and crew of employees at Fruition, a popular restaurant in Denver. Many of the people I have worked for and with are involved in or came out of restaurants and culinary projects. For me cheese has always been an extension of gastronomy, and the obsession with cooking and eating passionately. No cheese is an island, it should always fit within a wider framework of cuisines and agricultural patterns, ideally regionally specific and ecologically sound ones.

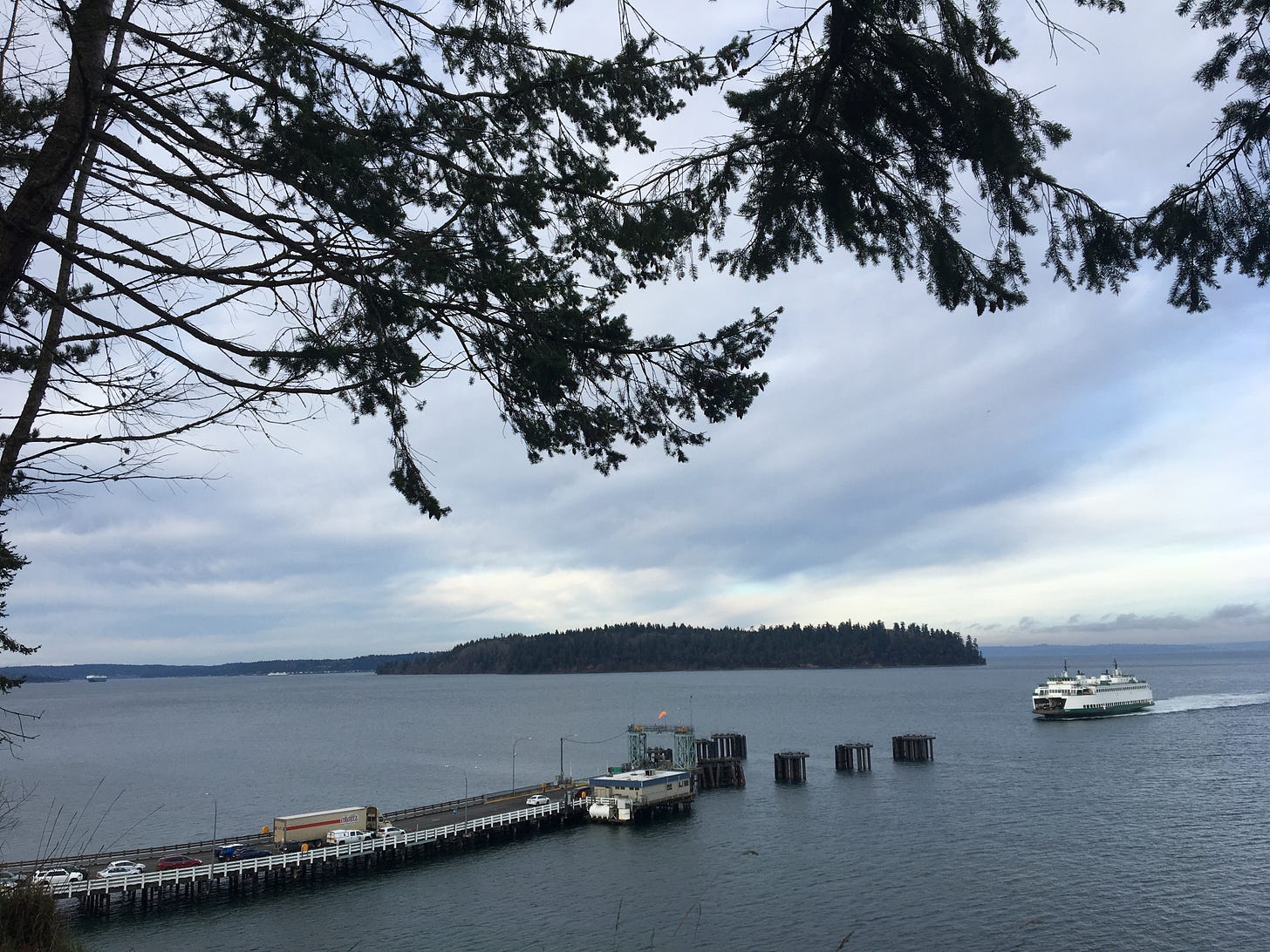

As the next year progressed, I slid into a familiar, recurring depression with corresponding social isolation and a downward spiraling, dismal outlook on life and my opportunities for growth. I felt uninspired, and got stuck with my tires spinning in the spiritual mud. This is nobody’s fault but my own. I turned to my favored form of salvation, trip planning then quitting my job and hitting the road in the escape pod that is my vehicle-home. After a job offer in Australia fell through, I took a cheesemonger position in Washington’s San Juan Islands. This effort to move into the world of selling cheese didn’t go too well. I am not good at customer service, or haven’t learned to be yet.

The San Juans were beautiful though, and I felt really good there, so I moved over to Orcas Island and took a job cooking in a pescatarian restaurant, nestled on the water at a crunchy resort on the far end of the island. I lived in a tent onsite, in a campground for employees with a communal kitchen and access to soaking tubs and a sauna overlooking the cold Salish Sea. I was taking a break from cheese, something that I have done a few times and would recommend to anyone experiencing burnout or a lack of motivation with their work or craft. This gave me time to reflect and consider my next move. To float in uncertainty a bit, not forcing myself down a path because I was devoted to a career or preplanned trajectory. I’ve never been much for committing to long range plans for my future, and have never felt pressured by my family or peers to do so. Thank God. This has allowed my life to sprout and branch organically, without a lot of forceful meddling from my rational, conscious mind.

There are deeper currents moving the ship. Not knowing what we want to do is just fine. It’s likely much worse to settle for a situation that doesn’t feed our souls. It depends on what you’re looking for, of course. I still don’t know what I’m looking for. I’m just looking around, browsing the aisles, sampling things, but not buying much.

Maybe I’m not looking for anything.

Maybe it’s ok to just enjoy the ride.

Because it is just a ride.

Take your time, and enjoy it.

Or rush around, and experience misery, anxiety, and the full gamut of emotions available for us to sample.

Either way, eventually the ride comes to an end.

The amusement park closes.

Until tomorrow.

I like your writing and attitude and invite you to visit Waldron Island, just beyond Orcas, if you are ever back in the San Juans with extra time. I hope to get 3 dairy sheep for my small 5 acres here, just to have dairy here. Sheep are easier to manage than goats, which I have had here before.

"Not knowing what we want to do is just fine. It’s likely much worse to settle for a situation that doesn’t feed our souls."

Wish they told us this at school !